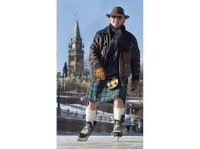

The White Stetson

/In 1946, a Calgary milliner created a white stetson for the annual Stampede that celebrated the city’s cowboy heritage. The “Calgary White Hat” proved to be so popular that it became emblematic of the city and the mayor began a tradition of gifting a white stetson for special occasions, including visits from dignitaries such as the Royal Family.

The white stetson was also a retirement gift to a long-serving city employee: Carl Burton Cummer who, in a 38-year career, rose from entry-level stenographer to the boss responsible for the overall management of the city. Ever a modest man, Carl would later observe that, “my advancement was not so much because of my abilities but possibly because of the knowledge and experience I gained from on-the-job training.” Those who knew him well would add that his thorough competence and attention to detail in everything he did was matched by an even temper and good humour. The Cummer family still has Uncle Carl’s white stetson — lovingly preserved in its original hat box from Smitbilt Hats (which continues to produce cowboy hats to this day.)

Carl was seven years old in 1910 when, along with his parents (Fred and Margaret), two brothers (Roy and Harold) and two sisters (Ada and Wilda), he moved to Calgary from Tilsonburg, Ontario. His two eldest brothers (Charlie and Jack) had come out to Alberta on a harvest train the previous year, and were so impressed by the opportunities available, they urged the rest of the family to join them out West. The family moved into a house on 13th Avenue SW, which was then close to the outskirts of town.

circa 1913. Back row: jack, harold, roy; front row: wilda, fred, carl ada.

Carl spent his summers at his brother Jack’s homestead in Youngstown, Alberta, where he enjoyed riding horses.

John W. (Jack) cummer at the tent on his homestead near Youngstown AB. (circa 1912)

In a biographical sketch of her father written six decades later, Joan (Cummer) Matthews would write, “When he was nine years old, Dad and Uncle Jack were riding on one horse and, just to show off, Dad tickled the horse and it bucked. He fell off and was hurt but was able to walk so everyone thought he was okay. But a few months later, he began to have severe chest pains and was often sick to his stomach. Doctors couldn’t find what was wrong with him, but the attacks became worse. At the age of 14 he was diagnosed as having tuberculosis of the bone. He was placed in the hospital and remained there for three months or so.”

While Carl was in hospital, the family converted a summer room over the back porch into a bedroom Carl could use year-round. It was furnished with a regular hospital bed and was very bright with windows on three sides. Friends came to visit him often, and they and the family worked out a code of doorbell rings so they could ring and go directly upstairs — the family knew who was visiting from the Morse code pattern.

Carl spent three years lying flat on his back in that room. He would practice the violin in a supine position, and his teacher agreed to come to the house to give lessons to her star pupil. He continued playing violin the rest of his life. When no one was around, he worked his way out of bed and tried to walk. One day, he astonished his family by laboriously climbing down the stairs. Feeling was returning to his toes. By the time his older brothers came home from the First World War, he was once again the life of the Cummer household.

The tuberculosis shortened his stature and affected his posture, but nothing could suppress his winning smile and the cheerfulness with which he greeted his many friends. Together with his Father and his sisters Ada and Wilda, he made the Cummer home on 13th Avenue a centre of warmth and hospitality.

Carl, Ada, Wilda and Fred w. Cummer

By 1925, he was able to join the staff of the City of Calgary as a stenographer clerk. In 1929, he married Ethel Larson, a switchboard operator who had been born in North Dakota. They had two children: Roy (b. 1930) and Joan (b. 1933). They bought a house on 28th Avenue SW, on the edge of the prairie where horses grazed.

He was a warm and loving father. His daughter Joan would later recount, “Dad is a perfectionist in everything he does and his gardens were no exception. Every row was perfectly straight. There were no weeds and he sometimes used tweezers to thin the vegetables.” As doting parents, Carl and Ethel eventually gave in to Joan’s desire to own horses. “In the Fall, Dad would let me bring the horses into the yard to eat the grass. I was generally quite good about making sure they didn’t get loose, but one day in my hurry to get to the bathroom, I didn’t lock the gate or tie my Candy Kid. When I came out, there was Dad sitting in the kitchen, having a cigarette. Very calmly he asked me if I had tied up my horse and locked the gate. The obvious answer was no, since there was Candy Kid in the middle of Dad’s garden, munching the newly transplanted flowers. It was the only year that there was a waver in Dad’s vegetable rows.”

Carl’s career in municipal administration followed Calgary’s rapid growth. The 1926 census put the population of Calgary at 65,291 (in 2021 it was over 1.3 million). Calgary was small and so was the municipal administration. The City Services department occupied the basement of City Hall. One of the most intense jobs at the time was to compile the list of voters for municipal elections. which required five months of work, typing, checking, printing, proof-reading and re-checking before the voters’ list was ready.

Carl was promoted from Stenographer to Records Clerk and, in 1944, to Assistant City Clerk under J.M. Miller. When Miller retired in 1955, Carl was promoted to City Clerk, where he was custodian of all official documents, a signing officer for the city and Secretary to the City Council. Each Council meeting would generate 200-300 letters from the City Clerk’s office informing or advising on matters that had been raised.

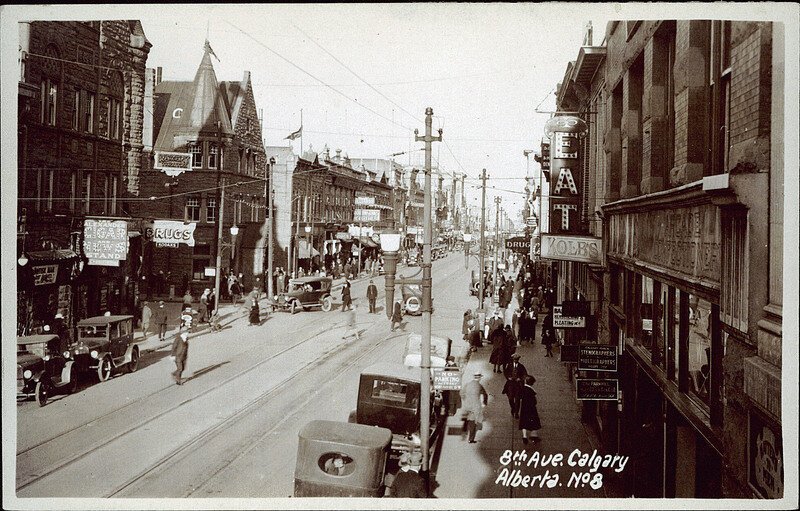

A natural born raconteur, Carl was always ready to tell stories about the early days of Calgary. In 1963, Carl told a reporter that, back in his earlier days, his workdays sometimes began by joining other passengers in helping to push a streetcar up the hill. “There were no traffic problems in those days and the only policeman on point duty was at 8th Avenue and 1st Street and operated a manually operated gadget to control the rush hour traffic.” As he neared retirement, Carl set down many of his reminiscences of Calgary’s early days, and some of his recollections will be the subject of future blogs.

The newspaper report noted that Carl was looking forward to his retirement. He was looking forward to getting his greenhouse established and to practicing on his Wurlitzer electric organ. He also anticipated spending time with his grandchildren. Carl and Ethel did indeed live long and happy lives together. Their house on 28th Avenue was a warm and welcoming home for family and friends and eventually they moved to a long term care facility near 17th Avenue NW. Ethel died in 1987; Carl in 1989.

Over the decades, Carl applied his writing and organizational skills to keeping in touch with the extended Cummer family and contributed many biographical pieces to the family history project launched in the 1970s. Much of those contributions furnish the material for these blogs. And the white stetson remains in the family as a reminder of his distinguished career and the sense of “Stampede City” fun he brought to everything he undertook.